This is Part Three of a three part series on professional and organizational maturity in the field of campus recreation by Grady Sheffield. It’s based on a presentation given by Sheffield and Bill Crocket at several regional and national NIRSA conferences. Read Part One here. Read Part Two here.

Thus far we have presented a new framework to view professional maturity that places value on the stage of maturation rather than age, seniority, position or area of specialization as a measuring point. It should be no surprise that if we begin to do this as individuals, our team’s maturity will also be affected, thus creating changes in organizational maturity.

Imagine a campus recreation department that has a history of existence operating as part of a kinesiology or physical education department but has recently moved under student affairs. The department manages outdated spaces consisting of a gymnasium, a small competition pool primarily used by athletics and an inadequate fitness area with limited amount of equipment. The staff is inexperienced, all of whom are in their first positions at all levels in the department. They work in silos and lack an understanding of how their work – programs and services – impacts the campus as whole. Fair or unfair, this department could be described as being organizationally immature.

Google search “organizational maturity” and you will find references to models that predict factors of performance based on an organization’s current maturity level. These models may identify varying maturity levels that might be defined as an evolutionary plateau of process improvement or a place in time in which the organization currently exists based on functions(s). Think about the previously described department. If we can agree on an organization maturity model that is based on impact, then we might agree the example department is most likely to be at a lower or beginning maturity level. Would it make sense that the department creating impact is at a high level? If so, then it would also make sense that low level impact equates to low organizational maturity?

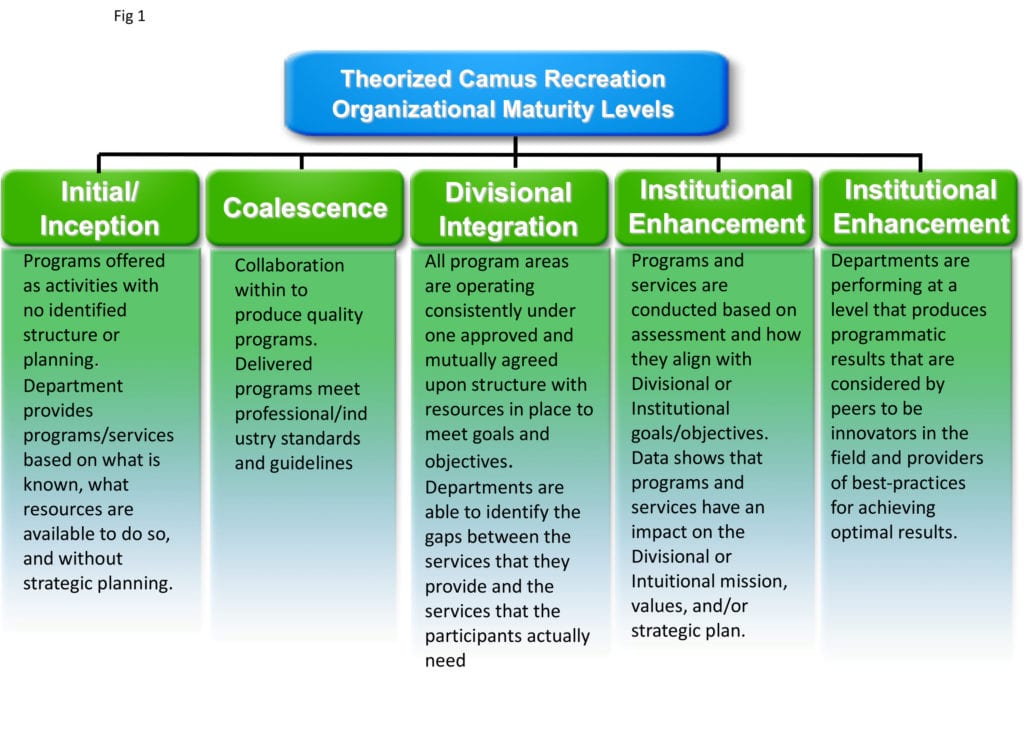

Each identified maturity level found in the models stabilizes an important part of the organization’s processes. In a simpler view, most people would agree organizations generally set out to grow or develop over time based on function. As they do this, they move or evolve from one level of maturity to another. Maturity models tend to focus on looking at five distinct levels; initial, repeatable, defined, managed and optimized. Through our own research on the topic, we have theorized there are five levels of maturity for campus recreation departments and have based them on impact rather than function. (Fig. 1)

In the Initial/Inception Phase, the department is mimicking peers and trends rather than making programmatic decisions based on operational enablement, or understanding the value of program offerings and leveraging buy-in. The department is siloed and does not focus on why they are doing what they are doing. Services are largely delivered in a vacuum without a comprehensive appreciation of institutional needs. Could this be our imaginary department described above? How much of this way of thinking/acting as department is impacted by the maturity level of the staff?

Eventually, that way of thinking or managing is replaced by coalescence, a coming together, at Level Two. At this point, departments begin understanding what they provide to their community – student development, leadership, health and well-being, etc. – is created and delivered by their programs. There is comprehension of which programs deliver what services. Departments are still, however, largely programmatically driven because of an unawareness of operational and participant needs, but silos are coming together and overlapping and strength begins to build within the department. Related to professional maturity, the staff members at this stage are most likely evolving into true professionals in the field.

As you continue through the five levels of maturity, the department begins to become divisionally integrated. Departments are able to identify the gaps between the services they provide and the services participants actually need – also compared to other campus departments – and then improve and further define services to meet those needs. The department’s role and value may still be unclear as it relates to the goals and objectives of the division. Again, the staff members in this department are competent professionals in the field and are beginning to evolve into student affairs professionals.

With a firm understanding of programmatic capabilities, services provided, and the needs of participants and the institution, departments are now operating as a functional organization of the university and have entered Level Four: Institutional Enhancement. The department recognizes its distinct capabilities and how to differentiate its services from other departments or units. The needs of the participants and institution have a strong influence over program and services. At the core of this level, the department is no longer viewed as a cost-center, but one that brings valueto the institution. Many members of this department are evolving to practitioners in higher education.

Departments that reach the final stage, Industry Optimization, clearly understand and articulate the way in which campus recreation programs and services enable institutional processes – goals/objectives – and ultimately create value for institutional constituent while also setting standards for their peers to follow. Departments at this level actually become value-add partners of their institutions and associations.

As stated before, student learning is our most important institutional outcome, but it must be achieved through on-going faculty and staff development (NASPA Leadership Exchange, 2013, p.14). As higher education continues to change and our roles as practitioners constantly evolve, we must mature as individuals and departments in order to stay ahead. Thinking about professional and organizational maturity should not be something that makes us feel unqualified or unsure of our abilities. Instead, it should challenge us to be more competent as higher education practitioners in the field of campus recreation in order to serve those impacted by who we are and what we do.